Tree Planting in Canada's Wild West

ARTICLEFEATURED

Sam McGriskin

9/27/20256 min read

bees, booze, trees, trips, blisters, butt hurts, ripped shirts, camp flirts, camp moves, camp grooves, seedlings, sump pits, quick shits, misfits and tendonitis

______________________________

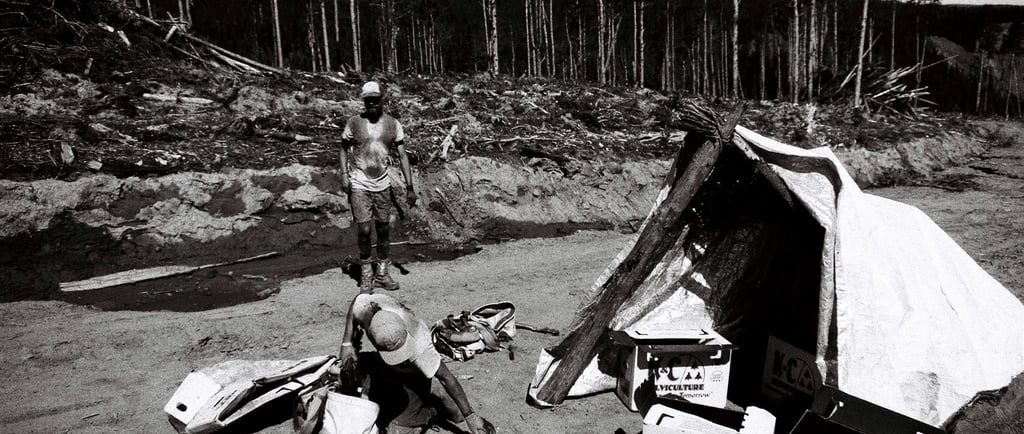

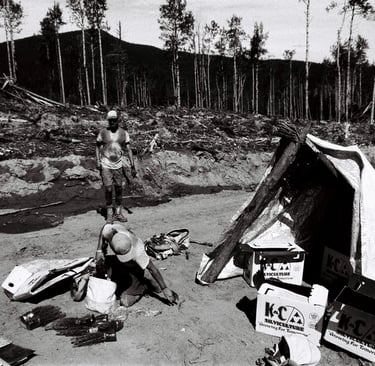

The job attracts a range of characters; from hippies looking for a nature-filled adventure to students desperately trying to pay their debts, to outcasts who started tree planting one day and never found a good reason to stop.

I went planting because I wanted to travel the country and do something new while making money. I was nineteen and uninclined to commit to school or a day job. Cousins of mine had planted, and one of them became a crew boss, so I asked him for a job. I had heard several stories about the nature of the work, including some that turned out to be tall tales.

My flight landed in northern B.C. in early May, and I was picked up with another first-year–or rookie–who sat in front of me on the plane (and whom I would end up planting with for years). The timing worked well because I hadn’t made arrangements to get to the camp, which was two hours from town. We drove there in the typical tree planting vehicle called a crummy, which is essentially the body of a bus welded onto a heavy-duty pickup. The crummy windows were covered by bars, giving it a prison bus sort of feel. My camp supervisor referred to the trucks as death machines.

When we pulled into camp, people were drinking around a fire. It was dark, and there was snow on the ground where we were supposed to set up our tents. I was unprepared and brought a cheap sleeping bag and no sleeping mat. The first few nights were cold and restless until I was able to buy better gear on our next trip to town. I used my sweater as a pillow and rolled over when I felt my side getting numb from the ground.

I felt motivated to be the best rookie, and my confidence lasted a few hours into the first day. I quickly and unknowingly incorporated the rookie stare into my repertoire. This consists of looking confusedly at the ground or staring off into the distance after a short while of searching for a good spot to plant a tree. My foreman told me to settle into a boxing stance before bending over instead of forming an acute angle. I planted fewer trees than many of the other planters, and the entire crew was told to stop at midday to replant our faulty trees. We were making 12 cents per tree and were not paid for replanting.

My crew boss/cousin had five seasons under his belt, and instead of planting thousands of trees every day, he now had to babysit a number of clueless first-years. Our crew had roughly fifteen planters, and only two or three were vets. Ideally, there are more vets who can take the rookies under their wing and teach them their ways. The company did its best to keep the boy-to-girl ratio to around fifty-fifty.

At first, many rookies plant under 1,000 trees per day, but they quickly improve. After reaching 1,000, it doesn’t take long to hit 1,500, then 2,000, and so on. If a planter doesn’t plant enough to earn minimum wage, some companies will then top them up. Our company did this for the first ten days of the season; after that, the difference came from the foreman’s pocket. At that point, the foreman would decide whether or not it’s worth keeping you on. At 12 cents per tree, minimum wage was around 1,000 trees at that time.

Some planters learn the job and become comfortable with working at an easy pace while making decent money; other planters push themselves and compete with one another, and some are in it for the money alone. One day, on the block, a Québécois planter yelled his simple but effective philosophy to me: “The ground is your bank, and the trees are your money!”

When there was no driving access to the block, we’d take a helicopter. We would usually fly in an A-Star, which is a five-seater that easily floats off the ground. The biggest helicopter we used was a Bell 205 I believe. It was a fourteen-seater and would chug back and forth during takeoff, making the whole experience more intense.

Riding home from the block, I often felt a sense of accomplishment. Our arms were dark from the sun and dirt and shiny with sweat. When we arrived at camp, there was a meal waiting for us. I was lucky enough to have great cooks every year I planted. The food was served out of a trailer or cook-shack through a cut-out window. The meals were different every night, and planters gathered in the mess tent and ate together. When the cooks were wound up, they would shoot tequila into our mouths with water guns from the cook-shack window.

My first bush camp was outside of Smithers, B.C. To get there, you drive about 40 km north out of town on a logging road, take a left, and drive another 40 km west, and you’ve made it. It was a gravel-covered opening in the middle of the forest. At the north end, there was the mess tent. Beside it, to the right, was the shower tent, with four shower heads separated by tarps with pallets to stand on. On the south side of the camp, by the entrance, was a long line of crummy trucks, box trucks, and fuel trucks. There was a red school bus that had been converted and had an office, a couch, and a bed inside. Between the trucks and the mess tent, there was a fire pit surrounded by miscellaneous chairs and couches, and about thirty feet east of the pit, there was a sparse forest ending at the road. In the forest, there was a maze of tents, clotheslines, hammocks, and other obstacles that you had to memorize if you wanted to safely navigate at night.

On a work day, breakfast was usually at 6 a.m. and dinner was at 6 p.m. Before eating, I packed a lunch, which usually involved a couple of peanut butter banana wraps, some fruit, and some block treats. During the bumpy drive to the block, there was often music playing in the back of the crummy, and many planters were sleeping or wrapping duct tape around their fingers for extra protection. Rage Against the Machine was playing on my first day. When the music wasn’t hooked up in time, a crew member of ours would always sing his passionate rendition of “Barrett’s Privateers.” Once we arrived at the block, our foreman would give us a map with our piece of land on it and go over the plan for the day. After that, everyone parted ways to their designated caches (pile of tree boxes).

A planting box often holds anywhere from 270 to 420 trees, and a common bag-up is about 360 trees (roughly 60 lbs). If a planter reaches 2,000 trees at 12 cents, they make $240. For 3,000—$360, 4,000—$480, and so on. By the end of the season, the highballers or pounders were often making $500 plus per day–and sometimes much more. The price per tree fluctuated depending on the difficulty of the land. The lowest tree price I received was 8 cents and the highest was 32 cents–while planting rough and steep terrain on Vancouver Island.

We worked three-and-ones (three days on, one day off), which is a common planting shift, though in the past it was commonplace to work five or more days in a row. On day three, it was booze night (time to get wiggly). Planters summoned what energy they had left and let loose. Some nights evolved into a booze-fueled dance party in the back of a five-ton, while others became a mushroom-induced night around the campfire.

The morning after a night off, planters lingered around the mess tent, and those who wanted to go to town hopped in a crummy. As the last crummy pulled out, there was often one frantic planter on its tail, just moments after falling out of their tent and scrambling to collect their dirty laundry.

A camp often held three crews, and over the course of the season, everyone would become close—especially with their own crew. There were a few camp moves during the season, and sometimes that meant losing a crew to another camp or gaining some new faces.

Some of the most memorable times were camp moves; everyone piled their tents and belongings into the foreman’s box truck and packed up the entire camp. Then we hit the road–sticking out like a sore thumb–to the new camp which was usually far away. There were often a few days off between moves, and planters stayed in cheap motels along the route. One motel room would naturally become the centre of the action and endure a mass of sloppy planters.

Planting is living in a remote place away from the real world and often having no internet or phone reception–everyone sitting around a campfire and talking without distraction.

It pulls you down and then props you up: if you’re young and looking for a gig that can earn you good dough and toughen you up, go tree planting. You’ll learn to push yourself harder than you thought possible and meet all kinds of friends and characters in the process.

RUNNING MAN PRESS

CoNTACT

info@runningmanpress.ca

© 2024. All rights reserved.

ads@runningmanpress.ca