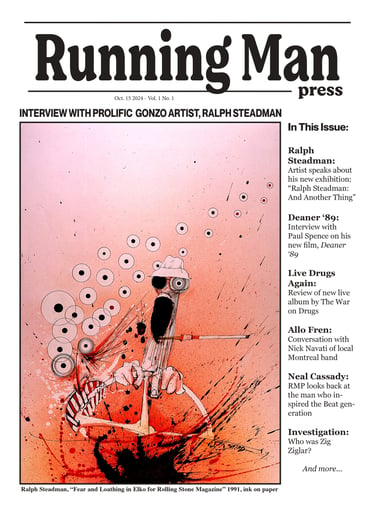

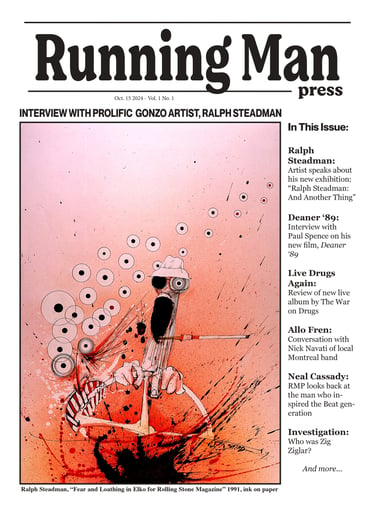

Vol. 1 No. 1 Interview: Ralph Steadman

INTERVIEW

6/16/20255 min read

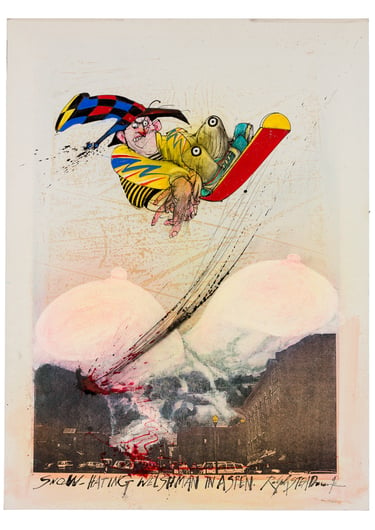

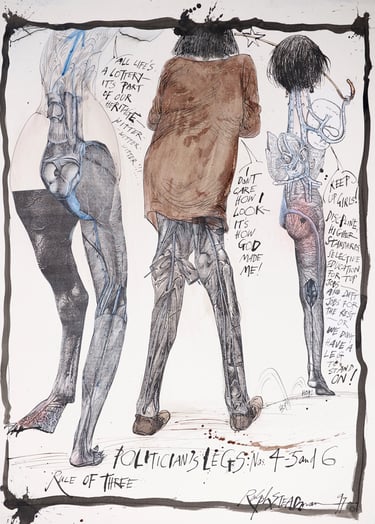

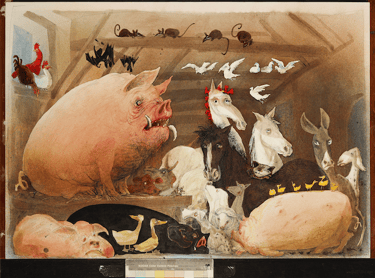

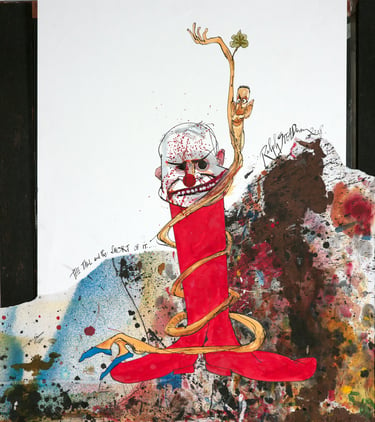

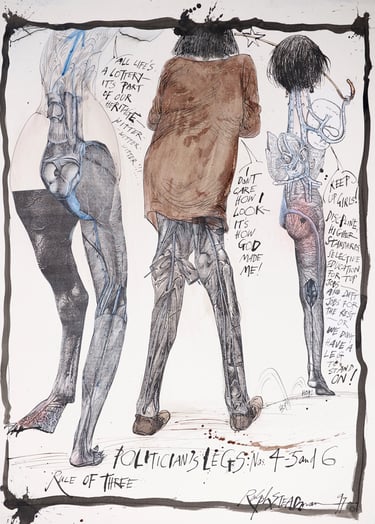

Ralph Steadman’s artwork is often chaotic, comical, gory and is always unique. He has produced a mountain of work over the last six decades; much of which can be seen in his exhibition, “Ralph Steadman: And Another Thing”.

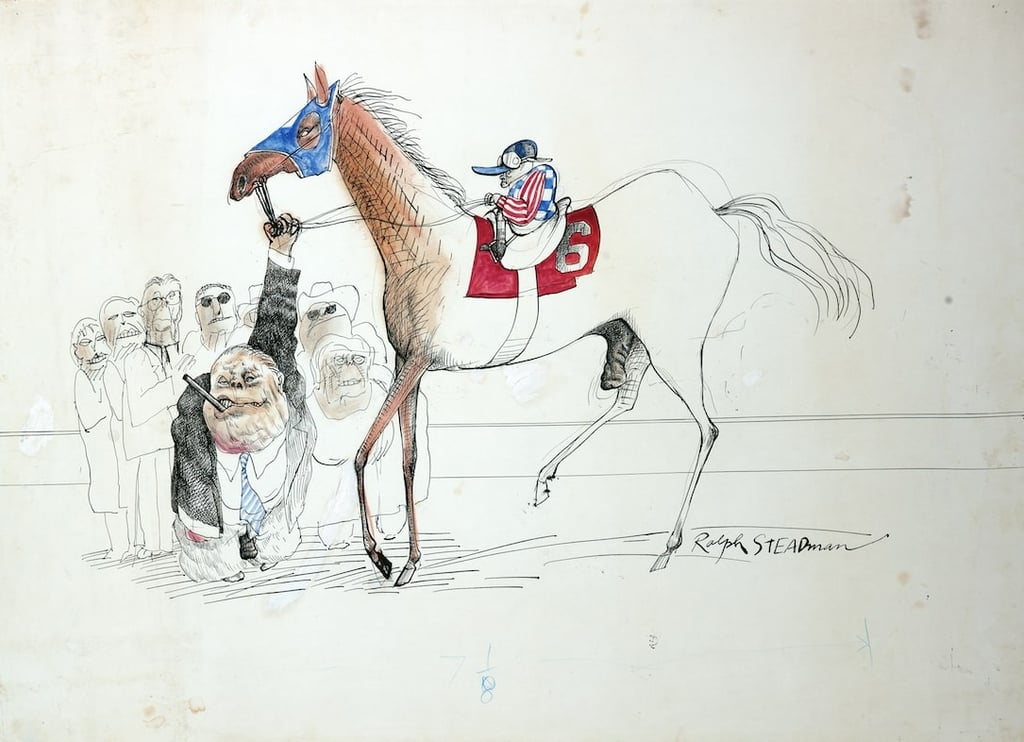

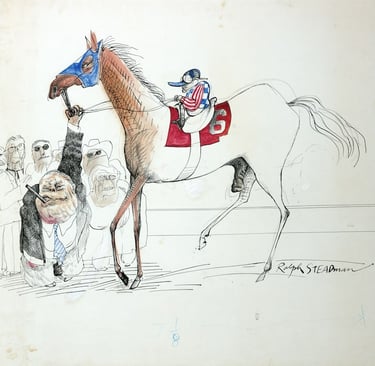

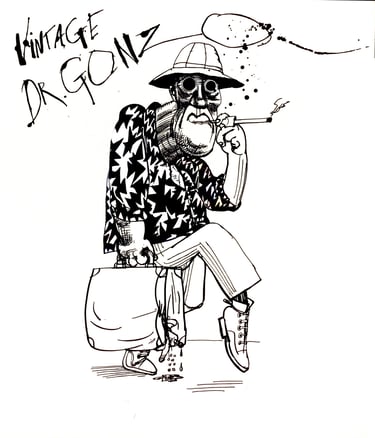

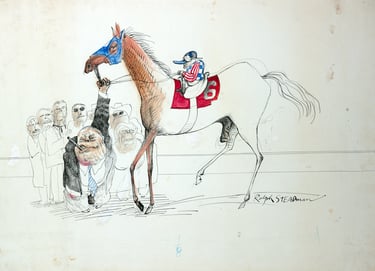

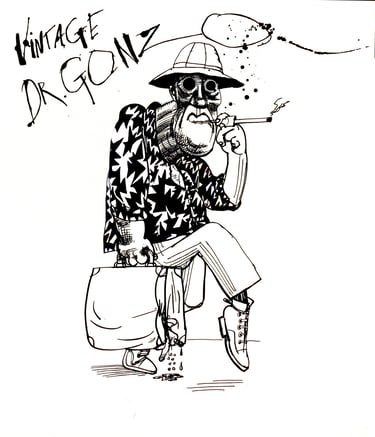

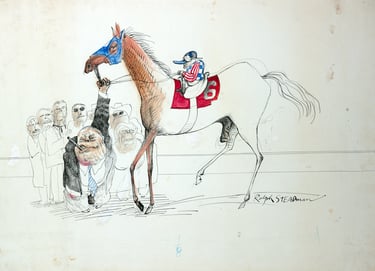

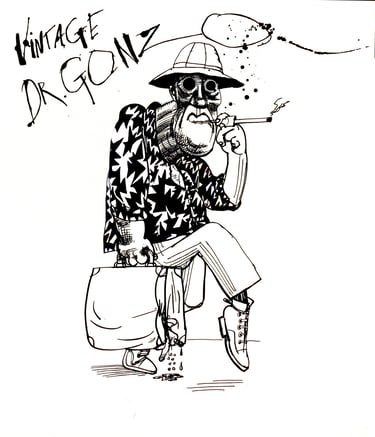

Steadman is likely best known for the work he has done alongside Hunter S. Thompson since their first meeting in 1970 when they covered the Kentucky Derby for Scanlan’s Monthly. Steadman made the illustrations for Thompson’s famous Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream, along with several other books and articles.

Born in Wallasey, Liverpool in 1936, Steadman took to making things at a young age, such as model planes, before he started drawing. Steadman went to grammar school in 1947 where he developed his great distaste for authority, later noting that “authority is the mask of violence.” He landed his first job as an apprentice aircraft engineer in 1952 and left after nine months, deciding that factory life was not for him.

Not long before beginning his National Service, Steadman happened upon an ad in a magazine that said, ‘You too can learn to draw and earn £££’s!’ He took the cartooning course held at Percy V. Bradshaw’s Press Arts School and then practiced his technical drawing skills during his National Defence where he worked as a radar operator as part of Britain’s ‘first line of defense’ against Communism.

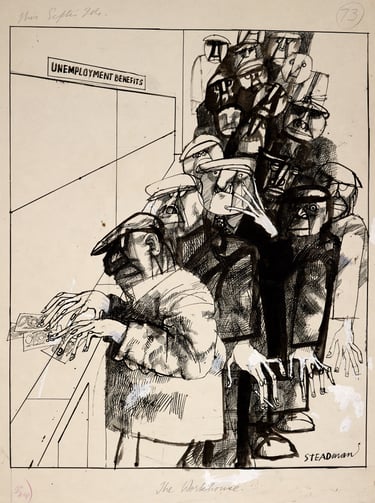

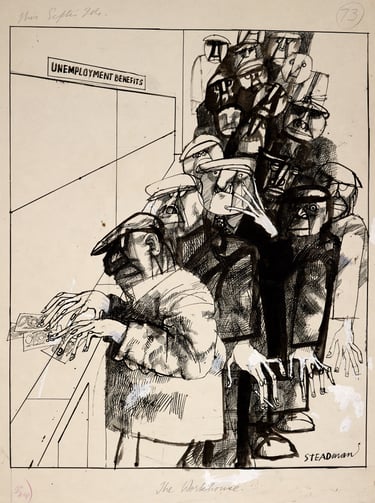

Before long, Steadman was sending his cartoons to several newspapers and landed a job with the Kemsley Group of Newspapers. He eventually became a regular contributor to Punch and began designing covers for the magazine in 1961. At this point, he was not satisfied with the demand for conventional cartooning:

“Cartooning wasn’t just making a little picture and putting a caption underneath. It’s also something else – a vehicle for expression of some sort, protest, or it’s actually a way of saying something which you can’t necessarily say in words.”

Steadman decided to make the leap to freelancing and was then able to work more freely. His art became more intertwined with politics and social commentary. In 1967, he illustrated Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland and his work was very well received.

About three years later, Steadman met up with Hunter S. Thompson to report on the Kentucky Derby. Upon their meeting, Thompson remarked, “Well they said you were weird, but I did not think you would be that weird!”

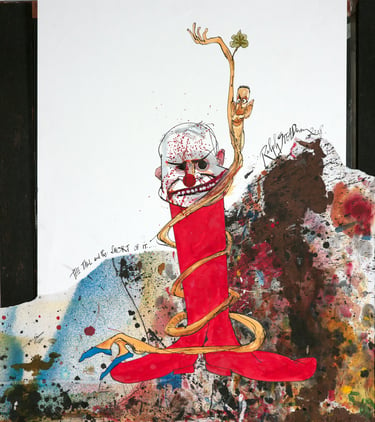

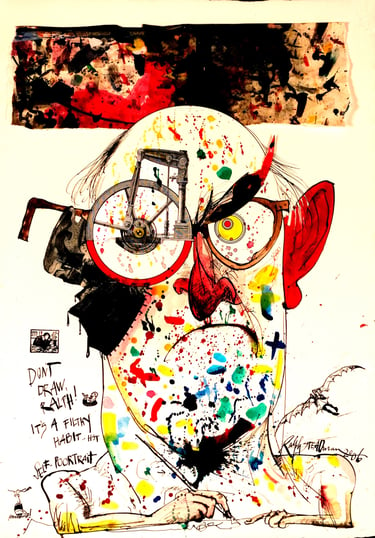

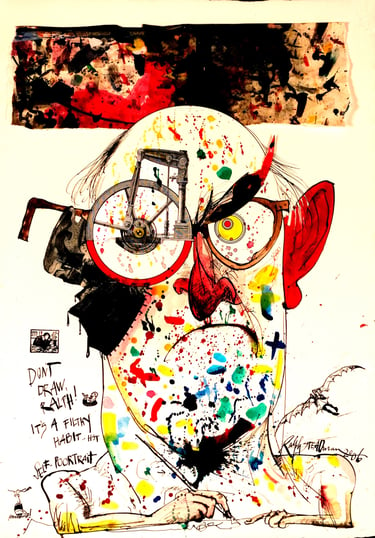

Steadman’s self portrait includes a quote from Thompson that says, “Don’t draw Ralph! It’s a filthy habit.”

The two were able to get themselves into a number of sticky situations. One day, Steadman began drawing someone at the Pendennis Club in Louisville – in a rather unflattering style which he learned Americans aren’t fond of – and a nervous Thompson told him to stop his “filthy scribbling”. The scene ended with the pair being forcefully escorted out of the joint after Thompson emptied a can of mace for safety purposes.

Another situation involved the pair setting out to spray paint “Fuck the Pope” on a yacht. When they were spotted by a security guard after noisily shaking the spray cans, Thompson set off two distress flares in the harbour, starting a fire on a nearby boat. The two then made their escape.

Steadman has since worked on multiple projects with Thompson and has published many books of his work including a book about one of his heroes, Leonardo Divinci, called I, Leonardo. He published three books about extinct or endangered birds and more recently created portraits of the cast members of Breaking Bad which were used for the DVD box covers. A documentary film about his life called For No Good Reason was released in 2012 and shows Steadman working quickly in his studio.

Steadman has completed more projects than can be mentioned here, which have led up to his most recent exhibition “Ralph Steadman: And Another Thing”.

_____________________

RMP: “Ralph Steadman: And Another Thing” covers over six decades of your work, from caricatures of presidents to distorted Polaroid pictures. What was the inspiration behind this exhibition?

STEADMAN: We were touring a retrospective of over 100 works in 2020 and because of the pandemic, we had to cancel the final two venues. When we were offered the support to put together a new touring show for the USA, we, and mainly Sadie, leapt at the chance to put together a brand new show. It starts in the very early days when I was learning to draw and includes work I completed last year so it’s a very comprehensive retrospective.

RMP: You have mentioned that you like to “distort and yet maintain the likeness” in your artwork. When did you begin to experiment with this approach?

STEADMAN: I think I always have, whether it’s a caricature of a politician or a Paranoid of someone famous. Sometimes it’s knowing how far you can take an image before it stops looking like its subject.

RMP: Would your artwork be more “normal” if you had never come across the work of George Grosz?

STEADMAN: What is ‘normal’? I react to things around me in a way that is normal for me and other people must like it, or respond to it, so is that normal for them? I have always liked the Dadaists and their challenge of what is acceptable as art. Marcel Duchamp is another inspiration.

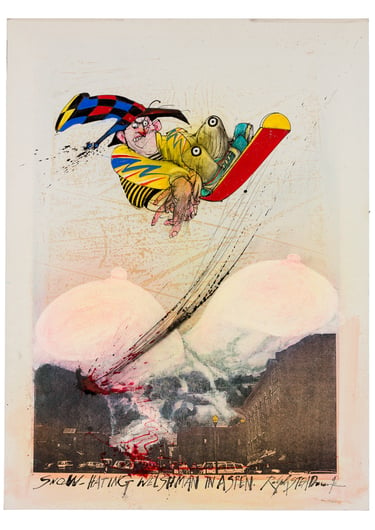

RMP: How did you come across the technique of creating “Paranoids”?

STEADMAN: We were on holiday with some friends in the town of TurkBuku in Turkey. I had my Polaroid camera with me and had been taking some pictures. In the heat, the emulsion in the photo melted a bit and I realised that there was a small window of time when the picture was emerging that you could manipulate the image. It was fascinating to race the clock and alter an image but still have it resemble its subject. I like the element of chance and the need for instinct instead of worrying about each mark.

RMP: At what point did you realize that you were onto something when first working with Hunter S. Thompson in 1970? What effect did you have on each other’s work going forward?

STEADMAN: We got on from the first and Hunter always challenged and pushed me. I hope I did the same for him. I think we could be braver with the other at our side. We did not worry too much about upsetting someone; we were just after some kind of truth and that was very liberating.

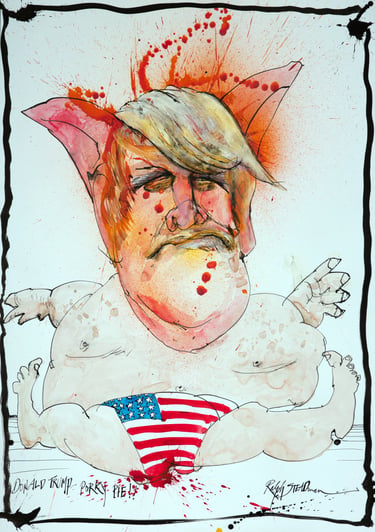

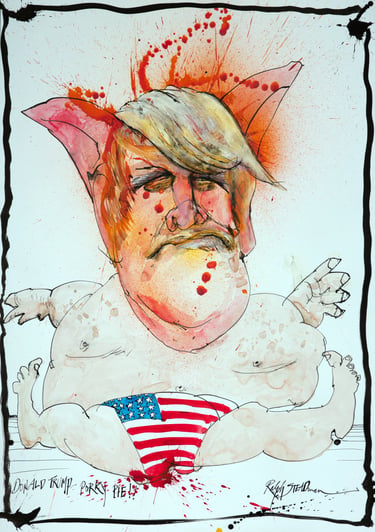

RMP: You are known for your caricatures of U.S. presidents. Which president do you feel you have been toughest on with your artwork?

STEADMAN: Donald Trump is a despicable human. I cannot find anything redeemable about him. So, I suppose his portraits are the vilest.

RMP: Do you have any more projects planned for the near future?

STEADMAN: Today we are launching an exhibition in the UK called INKling, at the Historic Dockyard in Chatham, Kent. Hopefully we can tour it across the UK. There is also a collaboration with a clothing brand called Neuw, which I think is going to be available soon.

Note: This was the first ever interview by Running Man Press. Initially, the chances of Ralph Steadman accepting the interview seemed slim to none due to there being no Running Man website or even a single issue released.

His PR man was easygoing but was sceptical. He asked for a PDF of the first issue, which was also non-existent. After staying up all night to bring one into existence, it was sent along. He asked for a list of questions to be sent by email.

Still assuming there was little chance of the thing working out, only seven questions were sent. This was done to increase the chances of the questions actually being answered but was likely a mistake. Regardless, the involvement of Steadman in the first issue, not to mention the permission to include one of his famous pieces of artwork on the cover, was a great honour and was almost unbelievable at the time.

RUNNING MAN PRESS

CoNTACT

info@runningmanpress.ca

© 2024. All rights reserved.

ads@runningmanpress.ca