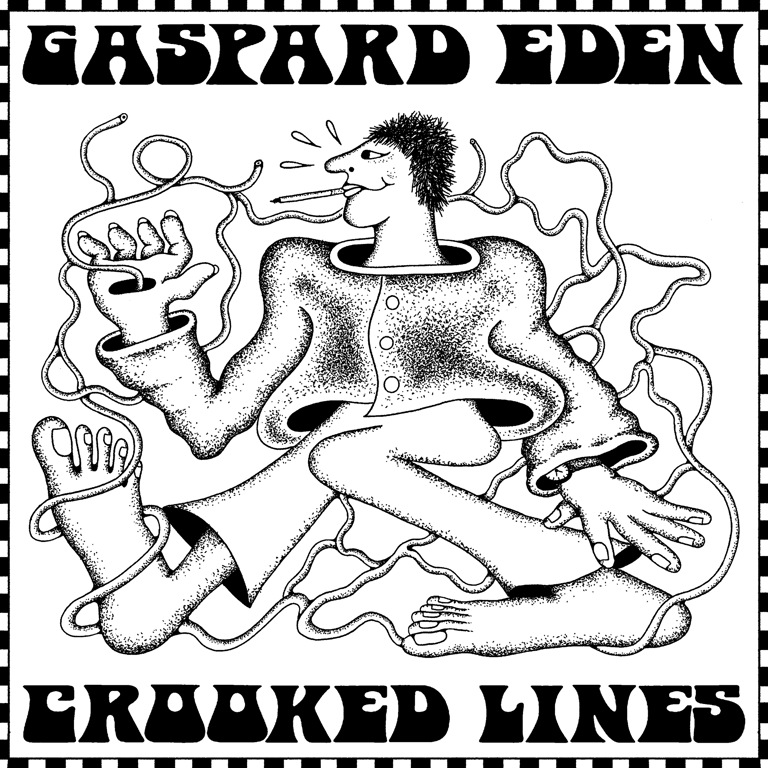

INTERVIEW: Gaspard Eden on his new album Crooked Lines

INTERVIEWFEATURED

11/28/202517 min read

Running Man Press - Vol. 1 No. 5

Gaspard Eden is a musician and an illustrator currently residing in Quebec City. Lately, his focus has been on completing his new album, Crooked Lines, which he recorded using analog equipment and a tape machine that he has learned to fix and maintain over the years. Eden played almost every instrument on the new album, which will be released on November 28th.

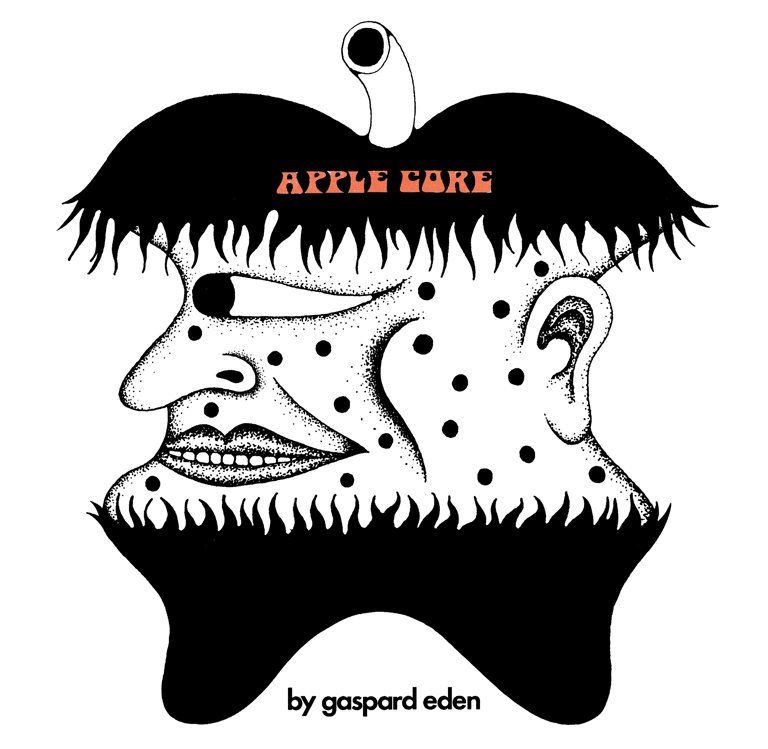

Eden provided the artwork for the cover of this issue, which is also displayed on the cover of Crooked Lines. Illustrations he created for the singles on the album can be seen throughout the paper.

_______________________________

RMP: Crooked Lines is coming out on November 28th. Was the approach for this album different from your first album (Soft Power)?

EDEN: Yes, so I did not record these songs the same way or write these songs the same way.

I would say that the reason it’s called Crooked Lines is because this is kind of a first attempt for me to do everything by myself. So what I mean by that is, with Soft Power, I had a team with whom I worked, I had a producer and then I had a sound engineer and then I had this and that, you know, a classic approach to recording an album.

But with Crooked Lines, this is the first time in my life I decided to kind of like plunge, and do the whole thing by myself.

RMP: You’re doing every part by yourself?

EDEN: Yeah. So, from writing the song to recording it, to mixing it, that’s what I mean by that. So it’s 100% DIY.

RMP: And you play all of the instruments?

EDEN: Mostly yes, except for drums. Aubert Gendron-Marselais plays drums throughout the album, except on one song, which is “The Model.” So if you listen to “The Model,” you’re going to notice snare and ride beats without the kick drum. And you can actually notice that it’s kind of finicky because I’m not a drummer, but this is actually how I wanted it to sound. I also have guest performances from my friend Raphael Laliberté (with whom I share ULF recordings) who plays Wurlitzer on “Cherry” and “In Your Car” and William Lévesque who plays Mellotron on “First Wave.”

RMP: I didn’t notice that the drumming was off at all in “The Model.”

EDEN: No? O.K. [laughs]

RMP: I did notice that one line in “The Model” says, “I’ll be your Crooked Lines.” Is that the only reference to the album title, or is there another song coming out called “Crooked Lines”?

EDEN: It’s the only reference to the album title. Actually, I came up with the album title before this song. So, I don’t know, it just inspired me in a way for that song. I like the term and how it sounds. So it’s kind of a little bit abstract, but at the same time, it has a lot of meaning.

As an illustrator, crooked lines kind of means something, you know, there’s something a little bit human about it, especially in the era that everything tends to kind of lean towards perfection.

And it’s really hard to, especially nowadays, I think it’s hard to accept imperfection and embrace it. The entire process of that album was recorded on tape. So when you record straight to tape, you have to live with all the tiny mistakes that you make. And this is the whole spirit of this album, you know, like the recording process, which was kind of a way for me to make peace with the skills that I have as a musician and as a singer-songwriter.

It was hard. It’s really a hard process, to record straight to tape, but it’s very rewarding in the end.

RMP: And that’s on your TASCAM 388?

EDEN: Yes.

RMP: And it’s in the studio, ULF Recordings, it’s called, right?

EDEN: Yes, yes.

RMP: It sounds like you know what you’re doing when it comes to mixing. Did you learn on your own or did someone help you out?

EDEN: I don’t know what I’m doing, [laughs] but I hope that it kind of sounds right. When you’re mixing and recording your own songs, you’re so invested in the whole process of it that at some point, you don’t have enough perspective to actually know what you’re doing because you’re so emotionally involved in the whole process. Since you’ve been listening to these songs like a thousand, a million times, at some point, it’s kind of hard to still remember the place where it’s coming from. So a song can evolve in many ways.

Some songs took two hours to create and then after that, I didn’t have to modify it in any way. And some other songs had like five different iterations. So it’s very kind of, I don’t know, it’s an interesting process to do everything by yourself. And it was kind of like a way for me to push my limits, you know, to see what I’m capable of in some way.

RMP: So, say you’re recording a song and it’s in the initial stages, do you take some time away from it to gain perspective, or do you finish it all at once?

EDEN: It really depends. There are a few songs that have been sitting for quite a while and most of the time, the reason they’ve been sitting for so long is because of the words. As a songwriter, sometimes I battle with words. So, that would be the main reason. And some other songs just fluently came to me, the songs kind of wrote themselves, you know.

But I would say that if I feel that the song has the meaning that it’s supposed to have, I’m not going to wait too long; I’m going to record it right away. Otherwise, it can become an object that I look at but I don’t really own anymore. So that’s kind of a trap, you know, because if you wait too long to finish something, this part that you had in the first place can disappear. And you’re moving on, you’re already somewhere else, but the song is still there.

RMP: When you say you get stuck on the lyrics, does that have anything to do with writing them in English at all? Or do you feel fully comfortable?

EDEN: I do feel comfortable when I’m writing. Writing lyrics in French is even harder. [laughs] To be honest.

RMP: Oh, really?

EDEN: Yeah, it’s such a different approach to songwriting, you know? I’m not going to get into the specifics, but English is pretty straightforward. If you have something to say, you state it, and it’s not going to sound wrong, you know?

But as for French, if you say something a little bit too straightforward, that can sound kind of like hard, and if you go too poetic, it’s going to sound cheesy. So it’s really hard to find the right stylistic approach in French because it’s super nuanced. I know that nuances in English are there as well. It’s not a way for me to say that French is harder than English. It’s just that for me, it’s very easy to sound cheesy in French. Very, very easy.

RMP: Will you continue to write everything in English in the future as well?

EDEN: Well, I’ve always written in English since I was a teenager. I kind of found a way to express myself through that language. But I would love to eventually explore my mother tongue, you know, since I’m a French-Canadian. We have such a beautiful musical culture here in Quebec, hidden French -Canadian gems. Beautiful artists. It’s just not an intuitive thing for me (yet).

RMP: Are you playing these songs live at all right now?

EDEN: Not at the moment. I’ve been working a lot in 2025. I’ve been producing other artists as well. I think I’ve been working on, maybe, four different albums at the same time. And, I also have illustrations, you know… a lot of stuff going on.

RMP: How often are you able to work on illustration now? I know you illustrate for all your own singles, but are you still making designs for other bands?

EDEN: A little bit less than before, 2023 and 2024 were big illustration years for me. But then, I started to work a lot on music. And I kind of naturally tend towards music more than illustration nowadays. I have a little bit less time to work on illustrations. Especially in 2025, but I still really enjoy doing it.

RMP: When you were a kid, were you always drawing or were you playing music as well?

EDEN: Both. Yeah, I was doing both.

RMP: And did you see yourself leaning towards a specific one in the future or continuing to do both?

EDEN: It’s always a balance between the two practices. When you’re super invested in something and you kind of get sick of it, you can go towards the other. And it creates a headspace, in order to continue the other one, you know.

Especially for my projects in which both practices come hand in hand. I like to illustrate for my music. And maybe one day make music for the illustrations.

RMP: You’re still living in Quebec City, right?

EDEN: Yeah, that’s where I’m based.

RMP: I’ve really only passed through as a tourist. What is the music scene like there?

EDEN: Well, it’s not like Montreal or Toronto or a bigger city, you know. It’s a small city, but it’s super alive in terms of the underground music scene. Here we have a place called Le Pantoum, which is kind of a complex where… this is very hard for me to elaborate on in English. I’m going to try my best.

So, this is a place that comes from people just like you and me, people who believe in giving back to the community by creating a space, especially for art, you know, and underground music. And being that place, it kind of evolved throughout the years towards a place where you can actually record an album. There are three floors; there’s a recording studio on the second floor, there’s a live venue on the first floor, and on the third floor, there is a smaller venue and also jam spaces for bands.

RMP: It’s all centred around music?

EDEN: Yeah, and it’s very interesting because I’ve never seen a place like that anywhere in the world. But I could say that this is kind of like the heart of the music scene in Quebec City. So, it’s worth looking into.

RMP: I’ve never heard of it, but I’ll definitely look into it.

EDEN: Yeah, well, Quebec City is still a small thing, you know. It’s almost like Disneyland for tourists. But it’s so much more than that as well.

RMP: Would you call yourself a perfectionist?

EDEN: Well, define perfectionism for me.

RMP: Maybe you tinker with things a lot more than you have to sometimes–songs or videos, whatever it is. And you take a long time to decide whether it’s right or wrong. Or is it more natural and you say, you know, “this works, that’s fine the way it is?”

EDEN: I would say 90% of the time this [perfectionism] is the case and sometimes when I’m lucky, I go into the 10%. It’s perfectionism, but not always in a good way.

RMP: I ask because I’ve seen your art, listened to your music, and it’s polished, but not overdone. And the live set on YouTube is the same. It looks like you spend a lot of time on the details.

EDEN: Well, that’s interesting, thanks for noticing that [laughs]. Yeah, I spent a fair amount of time just trying to attain a certain aesthetic–because it’s super subjective, you know–that in my head kind of surprises me. Because I really feel that if there are no surprises for the artist, there are no surprises for the audience. I would say that, yes, I tend to polish a lot. I don’t know if it answers the question, but I would say that I’m definitely a perfectionist.

And sometimes I’m really trying my best not to overthink something. And this is a trap there.

It’s like, when something starts to feel overdone, like overcooked or just a little bit too polished, you know? I’ve always been a huge fan of raw material. Like visceral art, something that kind of comes from a place where the right questions and the right answers were found, you know, and I think it’s very important to keep a raw aspect about the art that you’re making. It’s important to remember where it’s coming from and that the final aspect of the object that you’ll work on is still reflecting that somehow.

And you know, as I said, sometimes I tend to lose perspective, especially when I’m doing everything by myself. And sometimes a project can kind of get lost. You kind of get lost in the whole process of it. So yeah, that’s a learning curve for me as well. Sometimes I just convince myself that I’m not gonna linger too much before I record something because I want to move on, you know? But it’s easier said than done.

A lot of times I’ll be working on a song and it’s evolved a lot and then I come back to the initial demo or first time I laid down the idea and... that was it, you know? Now it’s too far, [laughs] I went too far with it. At the same time, it’s part of it. Now, I don’t really mind making big sacrifices in order to get back to the essence of something. If I have to scrap an entire song or erase an entire verse or redo the guitars in order to make it more digestible or closer to what I had in mind in the first place, I’ll do it. The thing that is hard is to keep in mind or remember what you had in mind in the first place.

RMP: For the rest of the album, which will be released this month, you worked on everything yourself as well? You didn’t collaborate with anyone?

EDEN: I did collaborate a little bit with a couple of my musician friends. I had my studio partner Raphael working on two or three ideas with me. He would come into the studio and hang out with me. He’s a super talented musician so he would, I don’t know, try something on the Wurlitzer and sometimes it changes the direction I was going towards.

Of course I relied a lot on the insight of a couple of my close friends. I would send my songs over and ask, “Is it any good anymore?” And sometimes they would give me little tips or advice in order to help me continue because perspective is really of the essence and sometimes it’s hard keeping it.

RMP: And you’re recording on the TASCAM and this other older analog gear. Does that become a headache when it inevitably breaks down?

EDEN: It’s more than a headache, [laughs] it’s a nightmare. I would say that when I bought the TASCAM, it was not working. I kind of got duped. I bought the machine and brought it home, thinking, this is gonna be super easy and I’m gonna start recording on it right away. Then everything was wrong. There were a lot of problems with the machine, and since it’s kind of a lost art amongst engineers, to maintain a tape machine, actually knowing how to calibrate and refurbish a tape machine.

It took me two years but I kind of learned about electronics on top of everything else. I was doing that day after day and still it was a part of the process of doing it by yourself. So, if I don’t learn how to fix this tape machine, the day is gonna come when it’s broken and I don’t know what I’m gonna do. Since I made the choice to build an analog studio with real analog gear, I have to develop the knowledge to maintain the gear because otherwise it’s just gonna fall apart.

Sound engineers back in the 90s, 80s, and 70s knew how to fix their hardware because otherwise no records would be recorded. It was a normal thing for them to have that skill. A calibration guy would come up into the studio before every session and calibrate the tape machine. Another guy would do maintenance; that was a normal thing. Nowadays, that’s kind of a lost perspective; people buy super expensive analog gear but they don’t know how to fix it. They spend a huge amount of money to fix the things when they break, it’s super expensive nowadays.

RMP: And finding the proper parts must be hard to do as well.

EDEN: Yeah, and also you really know how to use the thing if you understand the thing; how it’s built and what does what in the electronic schematic of it. There was definitely a creative process to it. I actually had to fix the thing that’s gonna be the recording device before I would record on it so that was part of the process of Crooked Lines as well. But still, that was a choice I made, probably because I’m a little stubborn but I really wanted to make it work.

RMP: And now you’re quite good at it?

EDEN: Yeah, I know how it works. I changed the capacitors in it, it took me about two years. It was very very long. At some point, there was a logical problem with it. The motor on it would work really weirdly, I would fast-forward and it would rewind, things like that. It was hard but with a little bit of help from people around me, I managed to fix the tape machine and make it as good as it can be.

RMP: Do you use computers for the final touches?

EDEN: If I could, I wouldn’t use any computer at all but nowadays it’s inevitably going to end up on a computer. So that stage, I do it by myself. On the TASCAM 388 there are only eight tracks, so I record everything I can on this, let’s say first batch of recordings. So I will max out all the tracks that I need and then after that I’m gonna dump that print–like 5 microphones, drums, bass and maybe a guitar. Then I would change tape and print a mix down of this entire thing I have on my computer in order to create more tracks.

So I have this mixdown on one or two tracks and I have six tracks I can work with if I want to add vocals and other instruments. After that second batch, I’m gonna dump it into the same session on my computer and sync it with the first batch so I have every track and I can work with all of that material.

I still mix in the box, by the way, because I don’t have a big studio mixing board because it’s too expensive.

RMP: And it has enough EQ and everything you need?

EDEN: Yeah, hopefully I don’t have to use any EQ at all because I got the sounds right but most of the time you still have to EQ a lot of it. I do use plug-ins and EQs in my computer when I mix in the final stage. But I’m really trying not to denaturalize the sounds that I recorded in the first place.

RMP: I read that Alex G’s album, DSU, was a big album for you. Is there anything else [musically] that has been even bigger or something new that you are really into?

EDEN: Aleg G’s album, if I can say something about it. I really romanticized the way that I came to know that album. I was actually in a record store and I saw that album and I didn’t know anything about Alex G when I discovered it. I actually, physically discovered that album, not on Spotify, not on Apple Music. I picked up that vinyl and asked the guy who was working there to put the vinyl on. I thought the cover was visually interesting and when I listened to it for the first time I was just blown away. It was so good. I really discovered something interesting in a very interesting way.

RMP: Since then, has there been anything that has kind of caught you the same way?

EDEN: That’s a good question. I would say that lately I’ve been listening to a lot of instrumental music. Like, Japanese... they call it environmentalist music. It’s experimental, almost like a new age type of music, very very soft and contemplative kind of music. I’m really, really into that nowadays.

I like the space of it... how you can exist between the space that resides in that music. It’s very interesting. So, I listen to a lot of that… Yoshio Ojima, Midori Takada, things like that... I still listen to Elliot Smith like every day of my life.

RMP: Yeah, I can see that connection.

EDEN: [laughs] I really enjoy the same things I did before and sometimes, I’m just trying to find out about artists that existed in that era, early 2000s, 90s, that I didn’t know about. I still listen to a fair amount of alternative rock music and early indie music. On streaming platforms, you discover a lot of music every day but what really resonates, that’s another thing, because we all get so busy and we’re all just a little caught in the grind of it.

There’s a lot of good new music out there, like a lot, and sometimes it’s hard to digest it. Sometimes I discover a couple of artists here and there and I really enjoy what they’re doing but I’m never going to get to that romantic way of finding out about an album in a record store like I did with Alex G. I really feel like the bond that you develop with new music really resides in a romantic place–how you found out about it. Going to a venue, not knowing about a band and finding out about them live; that’s another great way of falling in love with a new project. I do still believe in that approach a lot.

RMP: Is nostalgia an important part of your art and music, or do you consciously think about it?

EDEN: I would say, it revolves around it. Definitely. Nostalgia for me is like when I think about my dad, you know, and how I was kind of living through his entire fanaticism for music. We had so many records back home when I was a kid, and one of the first songs I heard was “Ticket to Ride” by The Beatles. I was surrounded by all of this.

This is funny because my dad... I’m just gonna take a minute to talk about this. My dad was a baby boomer; he was born in 1950, which makes him 25 in 1975, you know. So that generation would always listen to prog music, like Pink Floyd and Gentle Giant and Genesis and stuff like that but my dad was not into that. He was like a rock ‘n’ roller. He wanted to listen to Buddy Holly and Gene Vincent and all the 60s artists and the British Invasion, like The Who, The Beatles and all that stuff, so more early rock ‘n’ roll and also super romantic singer-songwriters like Roy Orbison.

So I kind of grew up on that music and that romantic approach to it always stood out to me. He had a Beta (Betamax) cassette collection, we had entire walls full of Beta movies and I would spend my days going through that collection actually watching movies that were from another era. So that was super interesting for me as a kid as well. I grew up in a certain way, I was fed with a certain cultural nutrition [laughs] from a different era. So I was nostalgic about an era that I didn’t even live and I kind of associate it with something that represents family.

I’ve definitely been very nostalgic about a lot of things and when you’re able to capture a moment or illustrate a memory you’re very fond of, it’s kind of like a small success in a way. It kind of touches on something that makes you more human, somehow, or more connected to yourself. You’re able for a moment to capture beauty somehow. Still, it’s very subjective... but in a way, it resonates with you.

RUNNING MAN PRESS

CoNTACT

info@runningmanpress.ca

© 2024. All rights reserved.

ads@runningmanpress.ca