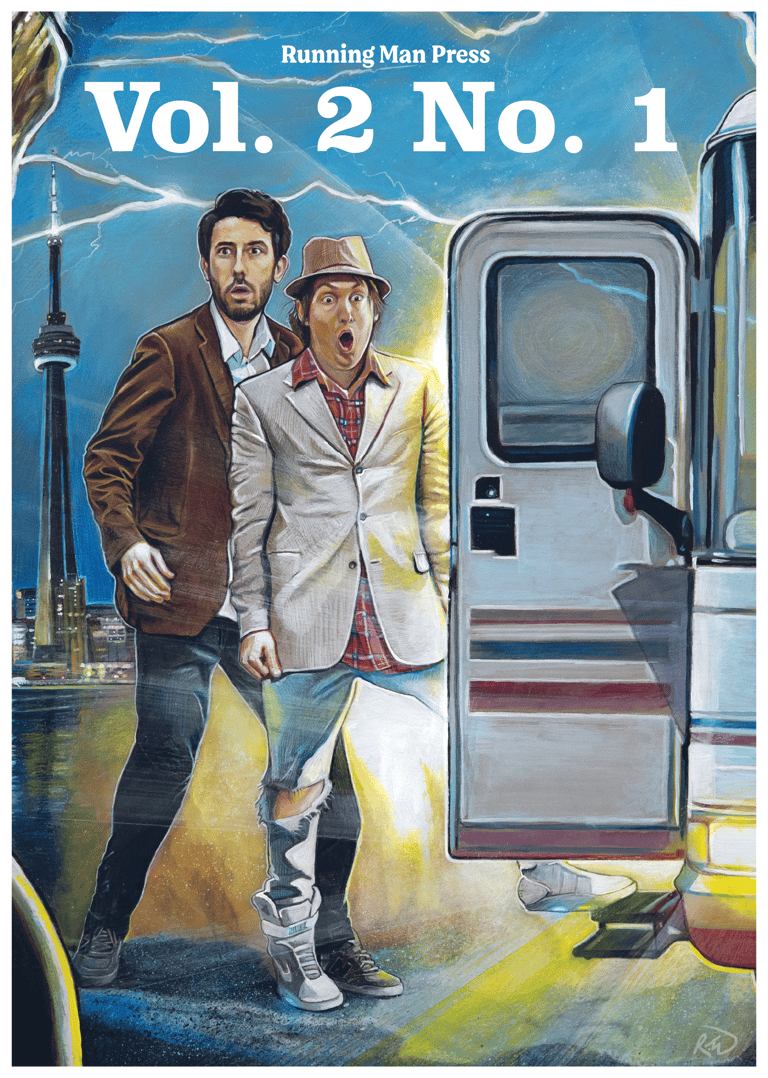

Illustration by Russell Treloar

NTBTS THE INTERVIEW: Matt & Jay on their new film Nirvanna The Band The Show The Movie

INTERVIEW

2/11/202617 min read

Matt Johnson and Jay McCarrol have been at it since they were teenagers. The current success of their movie can be attributed to the many thousands of hours of shooting, writing, editing, and improvising that Matt, Jay and their crew have been at for nearly twenty years now. The pair first released a web series, Nirvana The Band The Show (2007-2009) which included eleven mockumentary-style episodes ranging from ten to twenty minutes. In the series, fictionalized versions of Matt and Jay hang out in a Toronto apartment and scheme about how to play a show at the Rivoli. The show was picked up by VICE in 2016 and two seasons have been released since. Though the premise remained the same, a bigger budget and more time to work allowed Matt and Jay to take the project to new heights. The show has gained a cult following, and a third season is in the works.

It’s tough to explain the show to someone who has never seen it. It has nothing to do with Kurt Cobain and the whole thing revolves around two naive guys who are in a “band” without any real songs but who will do almost anything to play a show at a fairly ordinary bar (The Rivoli). In each episode, they come up with a new plan. The characters are very Canadian and are obsessed with and more or less living in the ‘90s in terms of the movies and video games they consume and the apartment they live in. The two are oblivious to the “real world,” though they constantly interact with it. In the show and in the movie, Matt and Jay are mostly interacting with real-world people and not actors.

A movie has been on Matt and Jay’s minds for some time, though the proper funding was not available until recently. Matt has directed smaller-scale films, including The Dirties and Operation Avalanche, but was given a chance to prove himself on a larger scale with the movie Blackberry, and he did just that. The movie was very well received, and in 2024, Blackberry became the most awarded title in the history of the Canadian Screen Awards.

A couple of things that set Nirvanna (the show and the movie) apart from the rest are: the subtle humor delivered by not-so-subtle characters, the real-life interactions that often bring out the best in people and the crew’s ability to accomplish and get away with wild things on a modest budget. Anybody who watches the show is at some point left wondering, “How the hell did they do that?”

Though some would argue that Nirvanna The Band The Show is the best show to come out of Canada (us), it has never really been brought to the mainstream until now and it’s exciting to know that the movie will bring Matt and Jay’s world to a large audience. Nirvanna The Band The Show The Movie is in theatres in Canada on February 13th.

The interview begins with Matt being handed a copy of the first issue of RMP, which features Ralph Steadman artwork on the cover and an article about Neal Cassady.

This Interview Contains Spoilers*

_____________________________

RMP: I brought a copy of our paper.

JOHNSON: Oh, so you’re Steadman fans?

RMP: Yeah, he was the first interview. This was our first issue, so it’s a little bit different now.

JOHNSON: Oh, I see, right, right, right, I got you. So this is from over a year ago now.

RMP: Yeah.

JOHNSON: I was just talking about Neal Cassady, in the context of homosexuality in On the Road, because somebody was telling me about how super straight the vibe of On the Road and Dharma Bums was, and I was like, yeah, yeah, but I think the whole subtext is that all these guys are trying to fuck Neal Cassady. That’s basically what it’s all about.

RMP: I think if you read the original book, which is a lot bigger, there’s more gay stuff.

JOHNSON: Oh, really? Oh, wow. I didn’t even know there was an original book.

RMP: He wrote it on that 120-foot scroll.

JOHNSON: Yes, almost everybody knows that. I make fun of that in the movie I just finished shooting.

RMP: Which movie?

JOHNSON: A movie about Anthony Bourdain [Tony], who was obsessed with these guys, and a Ralph Steadman, obsessive, obsessive.

RMP: Really?

JOHNSON: He was obsessed with Steadman, obsessed with Hunter, obsessed with all of these guys–when he was a kid… when he was a kid. I mean, it continues into your adulthood, but in this movie, he does a kind of On the Road...he arrogantly says that he also is going to write a book on one long piece of paper when he’s applying for a scholarship in the opening scene in the movie. But he’s not being sincere. But I did not realize that there was an original.

RMP: It’s just the unedited version.

JOHNSON: Badass.

RMP: I think they really had to edit it down.

In the movie, Matt, you say, “This is going to be a copyright nightmare. If you’re watching this in theatres, thank you lucky stars, because it’s gonna be the only screening.” So is this the final cut?

JOHNSON: What you saw isn’t. I’ve made a ton of changes for this cut, but none of them had to do with copyright decisions.

McCARROL: Remember when you said that? That was before we were able to get everything over the legal hump.

JOHNSON: That’s not really true.

McCARROL: Yeah, it was.

JOHNSON: When you say over the legal hump, what are you referring to?

McCARROL: Before we cleared everything. There were a lot of things that were sort of, legally in the grey area at the time, when we were saying that we weren’t sure. So, it was almost like a hopeful sort of thing to say at the time... if you do see this, if this does get made, my god, are you lucky to see it.

RMP: Was there any really good footage you weren’t able to keep?

JOHNSON: For legal reasons?

RMP: Or because it didn’t work with the plot.

McCARROL: Tons.

JOHNSON: Oh tons. Probably 5,000 hours of footage.

RMP: Is that because of the old plots that didn’t make it?

JOHNSON: No, it actually has more to do with what we thought we were going to need to shoot to make this story work; specifically, around the 2008 sequence, there were huge plot lines of us interacting with our young selves in and outside of that apartment that took us all around Toronto. Huge! Huge things that we shot that we, in the end, just didn’t need.

Everything we take out, we don’t take it out because we don’t like it. We take it out because the movie works, even without it. And a great lesson, I’m not sure if you’re a filmmaker at all, is that if–it works for any piece of art–if the thing still is intelligible to an audience with something removed from it, take that out. Take out anything that the audience doesn’t absolutely 100% need to get through the movie.

RMP: Like writing.

JOHNSON: Yes! Like writing, perfect example.

McCARROL: It takes a real discipline that we’ve been getting better at, because you really have to make a big sacrifice. You really need to prioritize what it is that you’re doing. You’re making the movie. Time matters. How clear it’s being really matters over how funny it is, which is crazy, but there are some of the funniest things that we’ve ever done that don’t exist in the movie because it didn’t help make the clear narrative sing.

RMP: So it’s not tight enough to be as funny?

McCARROL: You’re better off serving people a coherent movie and story than you are giving them just moments of funny–funny moments, because it just won’t count as much.

RMP: Matt, the character, finds out it’s 2008 because of what people are allowed to find funny.

JOHNSON: Sure, sure.

RMP: Which is great. Can you talk about filming that [2008 movie theatre] scene? And what was the hardest part of creating the movie’s 2008 setting?

JOHNSON: We were lucky in that we’re always, nowadays, looking for opportunities to put Nirvanna the Band fans in either the show or the movie, because there are enough of them in Toronto that we’re always trying to be like, “If you want to be in this, you can show up this time.” And so we had told everybody who showed up at that theater–we didn’t tell them what was going to happen–but that whatever they got shown, they should think it’s hilarious. And so that’s how we did that.

McCARROL: It was funny when we were getting them ready to just laugh for like, an infinite amount of time. And I remember Matt was saying to them, “All right, just keep laughing. Just keep going until we tell you to stop. It’s gonna be a while and I can tell you, I think this is going to get psychedelic. [laughs]

JOHNSON: And it did! Because we did it for so long.

McCARROL: The thing is, you can tell, once people were going, they were laughing, and then they can kind of just hear each other laughing, and then it turns into real laughter, which then was creating more laughter. And so the rolling out of the laughter was actually quite real, because it was just so bizarre.

RMP: So were you watching, not just that scene, you were watching a bunch of the movie?

JOHNSON: Maybe four minutes before that moment and we kept it going because we were shooting two cameras; one on the screen and one on Jay and I, right. But we shot a lot, and in terms of creating the rest of the world, every scene was different. So when we were on Queen Street, we didn’t really do much. We just sort of waited for there not to be people on iPhones and things like that.

But then, we were shooting at Yonge and Dundas Square. That was totally different, because we needed to know where those posters were going to be and what Jay was going to look at, like that would be much more technical.

RMP: You snuck the Blackberry poster in there.

JOHNSON: Yes, exactly, exactly, exactly. So we had to be much more specific, depending on what the environment was. We were lucky because–and we didn’t realize it–but that RV being a contained living room meant that we could still shoot in 2008 in the street, quote-unquote, but be in a protected environment where we can control everything.

So when we first stopped the RV, when we’re outside Yonge and Dundas, and I’m honking at Jay saying, “Get back in the car!” When we drive and hide the RV in a graffiti alley, all of that stuff winds up creating a feeling of 2008 when really we don’t need to show anything. And in that way, we just got lucky, we did not think that that was gonna be as valuable to us as it was.

RMP: I went back and looked at the real CP24 footage of Drake’s house/the shooting scene and you guys almost look like you’re just really focused on doing a good job on covering it [as a camera crew].

JOHNSON: I know. It doesn’t look like we’re having a very good time, does it?

RMP: Yeah, you also looked like you’re doing a great job.

JOHNSON: Yes.

McCARROL: If you were to see the actual layout of what that looked like, it was every single camera from every news organization in the city. There were like 50 of them lined up, and they were all in a U, pointed at the podium where the chief of police was speaking, and then behind the chief of police was just one of our cameras pointing the opposite way. And that was another... just a new moment of creating something bizarre–more bizarre than it being wrong. So even though we were getting some side eyes from all the police around, they didn’t even know what to tell us to stop doing.

RMP: You would have been running at that point right?

JOHNSON: Running away.

McCARROL: Well, I was running away, and it looked very suspicious, but then I would stop, and then walk back very confidently, as if this is completely normal. And by the time anyone was asking us, like, “What are you guys doing?” We were totally done with our footage.

RMP: This was during a Q&A, you said, “Get ready to watch this movie as a single episode without time travel.”

JOHNSON: Oh, yeah. Yeah, in season three you see what happens when we land in the SkyDome.

RMP: Season three isn’t finished, is it?

JOHNSON: No, we haven’t finished it.

RMP: Do you know when that will be out?

JOHNSON: No, it’s gonna depend, I would say, hugely, on how the movie is received when it comes out. It gets released by Neon and Elevation in Canada on February 13. And I think that what needs to happen is the movie needs to do well enough that a network wants to put season one and two on their platform, and then...

McCARROL: It helps our chances.

JOHNSON: And then season three would just come out after those first two seasons come out.

RMP: But shouldn’t that be almost easy by now, with your following?

JOHNSON: Maybe. You know, I personally haven’t pursued trying to sell the show to anybody as soon as we started down the road of making this movie.

McCARROL: There’s been some work that our whole team has been able to really dig into. And so it’s been hard to do everything at once.

JOHNSON: Exactly.

RMP: Work that you’re all included in?

McCARROL: Well, we all make Matt’s movies together, behind him in his crew.

RMP: The whole crew?

McCARROL: Yeah, the same Nirvanna crew made BlackBerry, we’re making the Bourdain movie, and there will be another VICE movie coming out.

RMP: In one interview, you talked about hitting the bull’s eye when it comes to crossing the line or not crossing the line with humor.

JOHNSON: Do you know what I was referring to? This is a concept of just humor in general, so I must have been quoting somebody.

McCARROL: Well, many comedians will speak on this.

JOHNSON: Yeah, this is basically the theory of what humor actually is, which is that there is a social...

McCARROL: Collective agreement.

JOHNSON: Yes, and that collective agreement says that you will not behave in X way, and humor, at least in some definition of it, is basically existing, literally right at the boundary of what that social convention is, so that everybody recognizes that you know you’re at the boundary and you know that they know.

McCARROL: And in doing so, that actually defines the boundary.

RMP: And pushes it.

McCARROL: Of course. Well, by defining the boundary normally, that means that you’ve stepped on it and you’ve felt where you feel people go, “Whoa,” and you go, oh, that’s the wall, perfect. Because if you get just there where you’re touching the wall, that seems to be where people generally get the most cathartic release.

JOHNSON: Well, and also where you can collectively experience something where you can all say without even needing to say it out loud, that is the boundary, and you can take some pride, and it fills you with a feeling of, ah, we have a boundary.

And it’s really great in terms of defining people with social disorders, or people who are awkward. Thinking about dealing with a stranger in that way helps you kind of stratify everybody, because somebody who is just, when you’d say, “Oh, this person’s out to lunch,” or you’d say, “this person’s weird,” or “I don’t like talking to this person.” Typically, it’s because their calibration of what that boundary is, is not matched to yours. And so a great way that we find: one, for making a movie like this, but also for talking with strangers, is trying to figure out what their boundaries are very, very quickly, and either staying within them or going to the edge of them to try to make them laugh.

McCARROL: Or when we’re in the privacy of our set or something and we’re improvising, what you don’t see is when we go too far.

JOHNSON: Right.

RMP: That’s what I was gonna ask, there must be a bunch of footage of you guys saying crazy shit.

McCARROL: There’s tons, there’s tons.

JOHNSON: Oh, tons of it, tons of it. It’s crazy.

McCARROL: And the thing is, is that, we aren’t being–by any sort of committee or people above us in a bureaucratic way–being, you know, cut off.

JOHNSON: Nobody censors us.

McCARROL: Nobody censors us. We’re censoring ourselves, because we can recognize when we watch something back and it feels, you know, too raunchy, like we don’t like it when it goes far beyond the line. Bringing it back to that bullseye, that’s what we aspire to hit. It’s just enough where it feels dangerously close to the edge because there’s a feeling that you get from that, and everybody, collectively, can kind of feel that and feel that they got away with something by experiencing it.

JOHNSON: You know, let me amend that. Everybody does it. That’s what makes it so magic; is that a group of people, they go, “Oh, yes, that’s it.” But, by the very nature of us defining it in a certain way, we exclude people, right? That’s why I think Nirvanna the Band is sometimes a very alienating show for people, because they go, “This is outside my boundary. This is not within my aesthetic standards. This is puerile.”

There are all these different ways that it is not acceptable to people. And so if it is, then that means, oh my gosh, you’re kind of getting it. And I don’t mean getting in that you are appreciating it for its brilliance–you are seeing a commonality and seeing the world the way that Jay and I see the world. And I think that is extremely pleasant. I refer to it as speaking in a code with somebody, where all the other people listening just think you’re a moron, but you’re actually communicating something very sophisticated.

RMP: So you guys actually were not caught with the parachutes at the CN Tower?

JOHNSON: No, it’s a miracle. The fact that they didn’t stop us and say, “take those parachutes off,” but instead focused on those little pliers...

RMP: Which is also crazy, that they let those in.

JOHNSON: I know, the whole thing is crazy, and it’s the reason that we had to go through with the jumping off of the CN Tower prank, because we did not plan on doing that at all.

RMP: Really?

JOHNSON: Yes

RMP: And once you get up there, one of the first camera shots when you go around is from the top, right? Is that supposed to be your cameraman, having gone up there?

JOHSON: Have you been up the CN Tower? You may, you may think there’s something else going on that’s not. So the way the CN Tower works is there are actually two layers that the public has access to. So that big bulge that everybody knows as the CN Tower is, that’s where Jay and I are. So we’re doing the edge walk around. There’s a second, tiny little–it almost looks like a golf ball–I would say maybe 150 feet up, which is also open to the public.

McCARROL: You pay an extra like 30 bucks to go up there.

RMP: Oh, my bad, I thought he had already gone to the top.

JOHNSON: And I think it has a special name. It may be called the observation deck

McCARROL: Or SkyPod?

JOHNSON: It might be called the SkyPod. And so Jared is just in the SkyPod and it is a failure of us in terms of...

McCARROL: We hadn’t established that, yeah.

JOHNSON: We wanted badly for that camera, Jared’s camera, to be moving between tourists in the SkyPod and us down there. And he did. He shot a lot of that, but the narrative momentum forbade us from spending that much time with the camera going between real people and us. I wish we could have but it just was an unacceptable amount of dead time.

RMP: Back in the day, you guys got in trouble for stealing the map–legal trouble [S02E07]. Have you gotten in legal trouble since?

JOHNSON: Yes.

McCARROL: Yes.

RMP: On that level?

JOHNSON: Way worse.

McCARROL: More.

RMP: Can you talk about...

McCARROL: No [laughs]

JOHNSON: Yeah, we’ll talk about it after the Jays win the World Series.

RMP: So you on stage Jay, that’s real footage of you and your band [Brave Shores]?

McCARROL: Yes.

RMP: Which is another example of blending reality with the fiction.

McCARROL: Which is something we’re always doing. In fact, sometimes we are writing around some of the available sets that we realize we can turn into sets or opportunities. The Drake shooting was one of them, where we showed up. And when you look around and there are helicopters in the sky, police tape and a whole news crew. That’s a very, very expensive and difficult thing to manifest for a film set. So it’s so much easier to just, you know, work with what’s there and realize that everything that is being given is like everybody acting perfectly all the time. So as long as you know how to sort of get in there and do the same thing as that live show, which was at the Budweiser Stage and on the streets. It’s everything. We’re always looking at the world as if it is an active set that is acting perfectly all the time.

RMP: Yeah, I’m surprised more new filmmakers don’t take advantage of that. Maybe they do though.

McCARROL: It happens sometimes. I think that we’ve done it for so many years that maybe people don’t realize how much prep we put into it, where we know what to expect and exactly how unpredictable reality is to work with as a film set. And so we know exactly how to sort of prepare ourselves for what we know is structurally sound and what we are prepared to be light on our feet, to just turn and rewrite and improvise with what’s been given to us.

RMP: How long have you two known each other? When did you meet?

JOHNSON: In high school.

RMP: So what were you doing before you had the cameras out? Or was that right away?

McCARROL: We were both messing around with cameras. When we met each other, we were both class clowns who loved attention and loved putting cameras on ourselves to mess around.

JOHNSON: That’s not true of me.

McCARROL: Well, you showed me videos of you and your friends making stuff. And it was, it had some like, you know, charm to it and you were editing and...

JOHNSON: But I wouldn’t have been in them.

McCARROL: You were, you had a couple. Well, I don’t want to put words in your mouth but I was going around with a couple of my friends making skate videos and emulating Tom Green pranks and stuff. But when I met Matt, he was the funniest person I’ve ever met. So I kind of just, I don’t know, [laughs] hitched my wagon to his star.

RMP: And when was the moment you realized you could actually make Nirvanna the Band the Show your “job”?

McCARROL: At first it wasn’t... it was never a job. We had jobs, but they were only one or two days a week because we were fine with living off of no money.

JOHNSON: This still isn’t really our job. This movie was a complete labor of love, literally 100% of the money of it went into the budget of making the movie.

RMP: So your other job is making other movies.

JOHNSON: My other job is, yeah, making other movies.

RMP: And music.

McCARROL: And music for movies and working on his movies, yeah.

JOHNSON: It would be great if one day this could be a job. Because it’s fun.

McCARROL: Certainly when we started out, it was just fun, and I know it’s almost like the cliché answer, but no, we had absolutely no idea that we’d be able to do it for years, nor would we even say that we would want to. We were just doing it to impress our very immediate group of friends, to get a laugh, and it was something that was just an outlet for us being just pretty silly with each other. And we were doing things already in public, like we would be in a lineup at McDonald’s, and we’d pretend like we don’t know each other, and we would kind of improvise a scene. There’d be no cameras, but we would sort of just use an audience, just like little menaces. Not to annoy people, but just because it created bizarre scenes. So we had an appetite to just do stuff.

–This interview has been edited for length and clarity

Running Man Newsletter

Get RMP updates, select articles, essays and goings-on

RUNNING MAN PRESS

CoNTACT

info@runningmanpress.ca

© 2024. All rights reserved.

ads@runningmanpress.ca